Table of contents

Table of contents- A complete guide to obsolescence management

- What Is Obsolescence Management?

- What are the main causes of inventory obsolescence?

- Principles of procurement for obsolescence management

- Demand forecasting in obsolescence management

- Supply rules according to the product life cycle

- Risk of obsolescence depending on the phase of the life cycle

- Impact of restrictions and rules on obsolescence

- Indicators to identify demand trends

- Conclusion: What should we take into account to minimise obsolescence?

- FAQs about Obsolescence & Obsolescence Management

Overview

Obsolescence management is a strategic approach to minimise losses from inventory that loses market relevance by identifying declining demand patterns, adapting procurement to the product life cycle (introduction, maturity, decline) and using tools like Pareto’s law and Economic Order Quantity (EOQ) to optimise stock levels and avoid costly surpluses, which are often caused by over-provisioning, inaccurate forecasts or market changes.

The new year begins and your company is determined to make a strong commitment to a highly innovative product with the potential to become the benchmark in its segment in a short space of time. The sales department predicts a resounding success and the procurement team, following this prediction, doesn’t want to miss out. They play it safe and fill the warehouses to cover themselves against stock-outs that would penalise sales. However, the market responds in an unexpected way; sales do not reach the expected figures and soon those products start to gather dust on the shelves.

What seemed like an ambitious strategy turns into a costly mistake.

This is a classic case of poor obsolescence risk management. Knowing when to stop restocking, managing expectations and adapting quickly to fluctuations in demand is essential to avoid excess inventory that leads to obsolete items.

In this article you will learn the basic principles for detecting declining behaviour in our products and, therefore, knowing how to stop the supply of certain items in time before they become obsolete.

What Is Obsolescence Management?

Obsolescence management is a strategic approach that allows companies to minimise losses derived from products that are no longer relevant in the market. This involves identifying patterns of decreasing demand, anticipating possible surpluses and adapting procurement decisions according to the life cycle of each product.

It is also about making informed decisions about which products to keep in stock and which to manage on demand, prioritising flexibility and profitability. Using tools such as Pareto’s law and strategies such as Economic Order Quantity (EOQ), the aim is to optimise investment in inventories and avoid the costs associated with excess stock, such as unnecessary storage and forced liquidations. We will look at all these issues in detail later in this article.

What are the main causes of inventory obsolescence?

Inventory obsolescence can arise for a number of reasons, including:

Over-provisioning

Buying large quantities of product without having an assured demand can generate unnecessary stockpiles in the warehouse.

Changes in market demand

The emergence of new competitors, changes in consumer preferences or technological innovations can make existing products less attractive.

Inaccurate forecasts

A poor estimate of demand can lead to excess stock, which has a negative impact on operational efficiency.

Inadequate management of the product life cycle

Failure to adjust procurement strategies to the life stage of a product — introduction, maturity or decline — increases the risk of accumulating obsolete inventory.

Supplier restrictions

High minimum orders or long delivery times can force companies to maintain higher inventories, increasing the risk that certain products will lose relevance before being sold.

Seasonal or fashion trends

Products with demand highly dependent on seasons or passing trends require precise management to avoid surpluses when their period of popularity ends.

Now let’s see how we can efficiently manage obsolescence in the company.

Principles of procurement for obsolescence management

The three questions we must ask ourselves in order to plan our procurement effectively to avoid obsolescence in our inventory are the following:

What do we stock?

It is essential to know what our assortment is (strategic decision) and how we carry out the procurement (tactical decision). This tactical decision will be what determines what I should stock and what items I should procure on firm customer order.

In the context of the strategy to minimise obsolescence, it is key to know when to stop the supply of a product, in the same way that it is also key not to be afraid to decide that a product, when certain rules are met, should be managed on demand.

And how do we make this decision? One of the most widely used tools for this is Pareto’s law, or the 80-20 rule. This theory tells us that there are a few items that account for a large part of the turnover and then there are the ‘long tail’ products, whose contribution to profits is much lower. This means that there comes a time when increasing the assortment is not synonymous with more profitability, since the income can be exceeded by the costs derived from the possession and management of more items.

This does not mean that all ‘long tail’ products should be managed on demand. We all know that, sometimes, in order for our customers to end up buying the most profitable products, they have to be shown a wide range of products. However, why is Pareto’s law important in assortment management? Because we should not – or at least should not – assign the same level of objective service to a super A reference as to a long tail product.

A high level of service has a very big impact on the safety stock that we are going to have for each of the SKUs and, therefore, on the capital that we are going to have invested in each product.

How do we procure? Management against stock vs. management against order

This is a key and strategic decision when it comes to taking control of our procurement. That is to say, deciding what part of the assortment we are going to have in stock waiting for demand to arrive, and what part of the assortment we are going to wait to have the firm order from the customer before launching the purchase order to the supplier.

Stockpiling has the advantage of agility to deal with unforeseen demand and to be able to maintain your target service level. And what are the disadvantages? Stockpiling is not free and also entails opportunity costs and the risk of obsolescence due to the volatility and changing nature of demand.

Other factors to take into account when deciding whether to keep an item in stock are its frequency of sale, the profit margin, whether there is a large number of customers who buy it – which minimises the risk of demand suddenly disappearing completely – the possibility of returning it to the supplier… All these variables influence stock decisions.

When do we stock up?

Let’s now review concepts whose definition we need to be very clear about when we carry out the procurement of our products and want it to be as optimised as possible.

Product coverage period

The first of these is the product coverage period. The coverage period is key when we talk about when to procure, that is, when we schedule purchase orders for a reference. The coverage period is made up of the sum of the internal review time and the supplier’s delivery time. The combination of the internal review period and the delivery time will result in a number of days.

Internal review time

Specifically, the coverage period is made up of two concepts. The first is the internal review time, which consists of how often, in an ideal scenario, a review is carried out to determine whether or not a reference should be procured.

Delivery time

And the second is the delivery time, which is defined as the time that elapses from the moment the order is placed until the merchandise is available in the system for sale.

This means that it is entirely possible that two different suppliers for the same reference can mean two different coverage periods. To understand this, the coverage period of an Asian supplier will generally be longer than the coverage period of a local supplier, so generally stocking up from Asia means having to take on more stock in our warehouses.

Procurement level

The procurement level can be treated as the order point which, of course, must be up to date. And to keep it up to date, what should I pay attention to? Specifically, to two parameters.

Forecast of coverage period

We need to know what the expected demand is for the coverage period. This value is 100% dynamic. That is to say, an item with a very stable demand is not likely to have significant variations. With an item with seasonal demand, on the other hand, depending on the time of year, the forecast to be covered in that coverage period will be very different.

Safety stock

Safety stock should be able to cover fluctuations in demand and supply. As with the forecast in the coverage period, it is 100% dynamic, and therefore to obtain the full benefit of its application, it must be kept up to date.

In this way, the sum of the forecast in the coverage period and the safety stock is what will indicate the level of supply of a reference, at a given time and based on specific supply conditions (that is, based on a specific supplier and certain determining factors of the safety stock and the service level that we will now see).

How much do we stock up on?

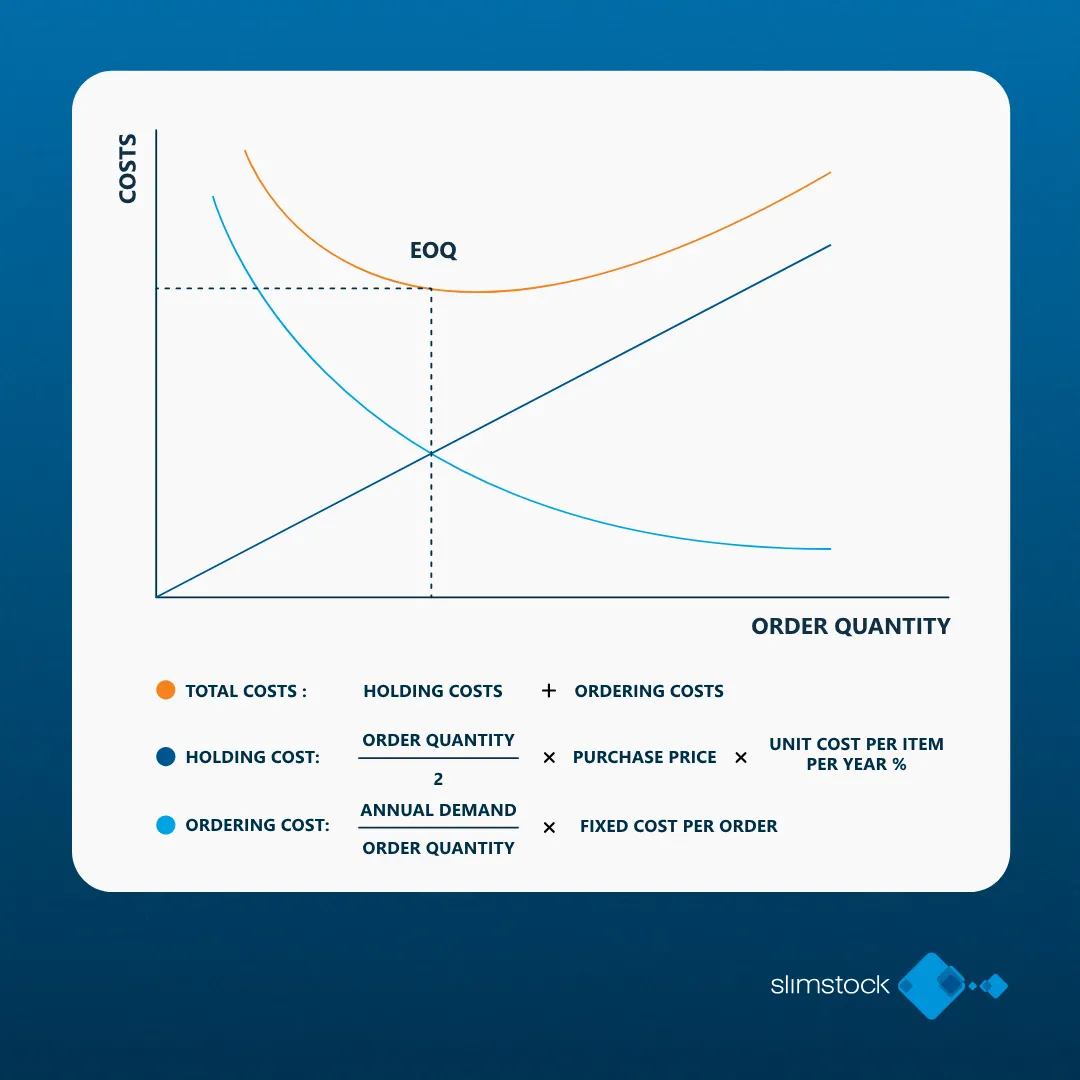

And obviously, when it comes to stocking up, we can’t forget how much we are going to buy. Do I stock up in large batches? Or do I stock up in small batches? Both options have pros and cons, but to find the optimal point we will resort to the optimal order batch or EOQ (Economic Order Quantity).

Economic Order Quantity (EOQ)

The EOQ graph shows us that as the purchase batch gets bigger, the cost of ownership increases, as a higher average stock level has to be managed. On the other hand, as I buy in larger batches, the management and ordering costs decrease.

Why? Imagine that on 1 January we decide to buy everything we need until 31 December. In that case, and taking it to the extreme, the person who buys would only have to be paid for one day’s work and we would only have to issue, receive and place one order. Obviously we are talking about an extreme case. But think about what it means in terms of a greater number of orders, a greater number of receipts, locating material, managing invoices…

Therefore, where is the optimum point that optimises integral costs? At the point where the costs of possession and the costs of ordering intersect and, therefore, the total cost curve is minimised and therefore that is where the EOQ is found.

Demand forecasting in obsolescence management

Keep this in mind. At most, only 10% of SKUs are stable and their periodic variability in demand is small enough that their instability does not affect inventory management.

Does this mean that we can only control 10% of the SKUs? Absolutely not. What it means is that only 10% of the SKUs will not have problems if I set a static reorder point and forget about them. What happens with the rest? They require active control of their reorder points and this needs to be adapted to their reality at all times. Seasonal factors, trends, irregularities… appear in our references and therefore their supply levels require our attention in order to adapt to them.

Something that seems as obvious as the fact that the supply level of seasonal references cannot be the same throughout the year… unfortunately it is not always the case. And during part of the year we are in excess and during another part we run out.

Therefore, throughout its life cycle, the demand for a product is changing, so it must adapt to this reality to get the most out of its operational management.

The consequences of not being agile in managing these levels of supply can be imagined to go in two directions: stock outs and excess inventory. In this article, we will deal with the second assumption, as it is the one that has a direct impact on obsolescence.

The definition of what is and what is not excess varies greatly from one company to another. If you are not clear about this in your company, consider this reference: we talk about excess stock when we have stock to cover more than two coverage periods, plus safety stock.

Don’t be alarmed if you have never done this before and the result that appears is bulky… the first thing is to know the starting point, and that it is accurate.

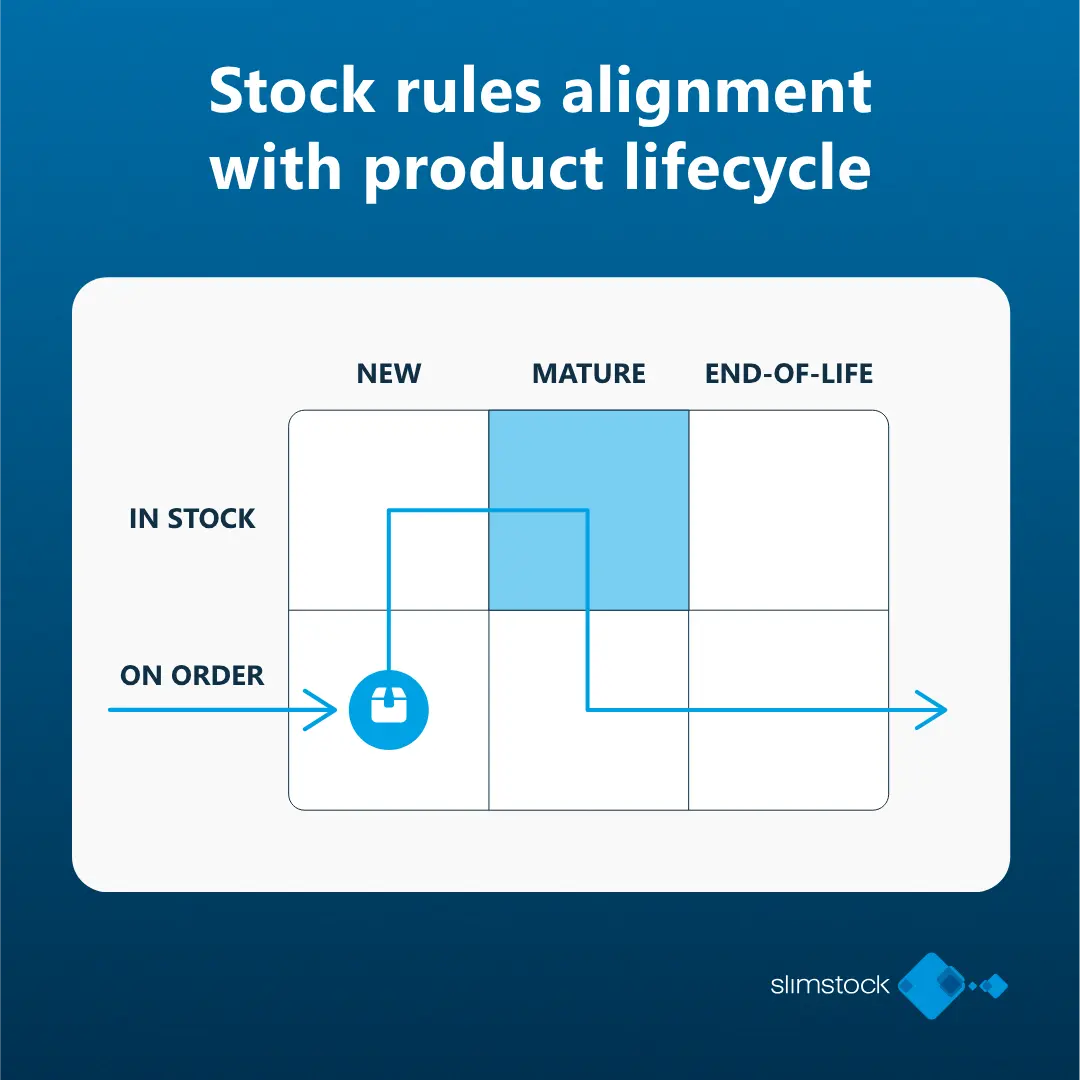

Supply rules according to the product life cycle

Let’s now look at how to adapt easily applicable supply rules to the references depending on the stage of the life cycle they are in. Throughout its life cycle, the demand for a product changes and with it its supply needs.

Introduction or Phase-In

What would be ideal when introducing a reference to the market (Phase-In)? Well, to have no stock. Remember that we still don’t know how the reference will behave in the market or how it will work, so, whenever possible, we will introduce it on demand. This is ideal, since the risk assumed in this way is very low since the stock is still maintained by the supplier.

What happens if it is not possible to carry out this initial management on request? We must seek to minimise the initial impact on our company. Therefore, if we cannot manage the reference on request, we will try to get the supplier to provide us with as much flexibility as possible (whether the reference is doing well or not doing well in the market) and thus minimise the risk of obsolescence. Our recommendation in this case is to look for a local supplier, who can provide this agility and who does not force us to commit to excessively high minimum purchase quantities.

As the new reference begins to have a certain stability in its demand, but without yet being able to be considered as a mature product, the risk of obsolescence begins to be mitigated. It is at this point that our order of priorities when it comes to procurement may change. At this point, we will begin to be less concerned about larger purchase lots as long as they translate into a better purchase price.

So, once the risk phase has been managed, new supply channels can be explored that will enable the purchase price of the product to be reduced. In practice, longer delivery times and larger purchase lots can be assumed since the stability of demand will enable this to be done and thus you will be able to benefit from more favourable purchasing conditions.

Mature items versus stock

The ‘mature against stock’ phase is the optimisation phase, it is the phase where we are going to manage the least risk and therefore we can consider both optimising the costs of the reference and maximising the service we give to the customer.

In this phase the items are perfectly suited for the application of EOQ (optimal order quantity). Stability in demand allows service level policies to be maximised. In fact, it is at this stage that items can be optimised at an operational level, both in terms of maximising service levels and reducing operational costs. It is important to take seasonal and trend patterns into account. Finally, it is also advisable to automate the management of these items as much as possible, as this minimises the risk of obsolescence.

Product decline

And finally, we come to decline. As soon as we detect that the behaviour of demand for the product is starting to follow a negative trend, the first thing we are going to do is be less aggressive with the target service level established for that reference. This policy of a lower target service level is going to have a direct impact on the safety stock. This will mean reducing the level of stock we keep of that reference.

The next step, if demand maintains its negative trend, will be to slow down procurement and, if an order needs to be placed, to place it for minimal quantities. Once procurement has been slowed down, we must define our new strategy. How are we going to sell the units we still have in stock? My advice at this point is to continue to maintain a good demand forecast for the reference. This will allow us to have information on the time coverage we have with the stored units.

Based on this coverage, the range that opens up is wide and depends, as I said, on the company… but the objective is common, and that is to try to sell these units with the least possible discount: Positioning on the web platform, encouraging sales representatives to offer it, making small discounts, including it in packs with other products, introducing it in the outlet channel or even selling it in the last instance to companies that are precisely dedicated to this, buying surplus stock from companies.

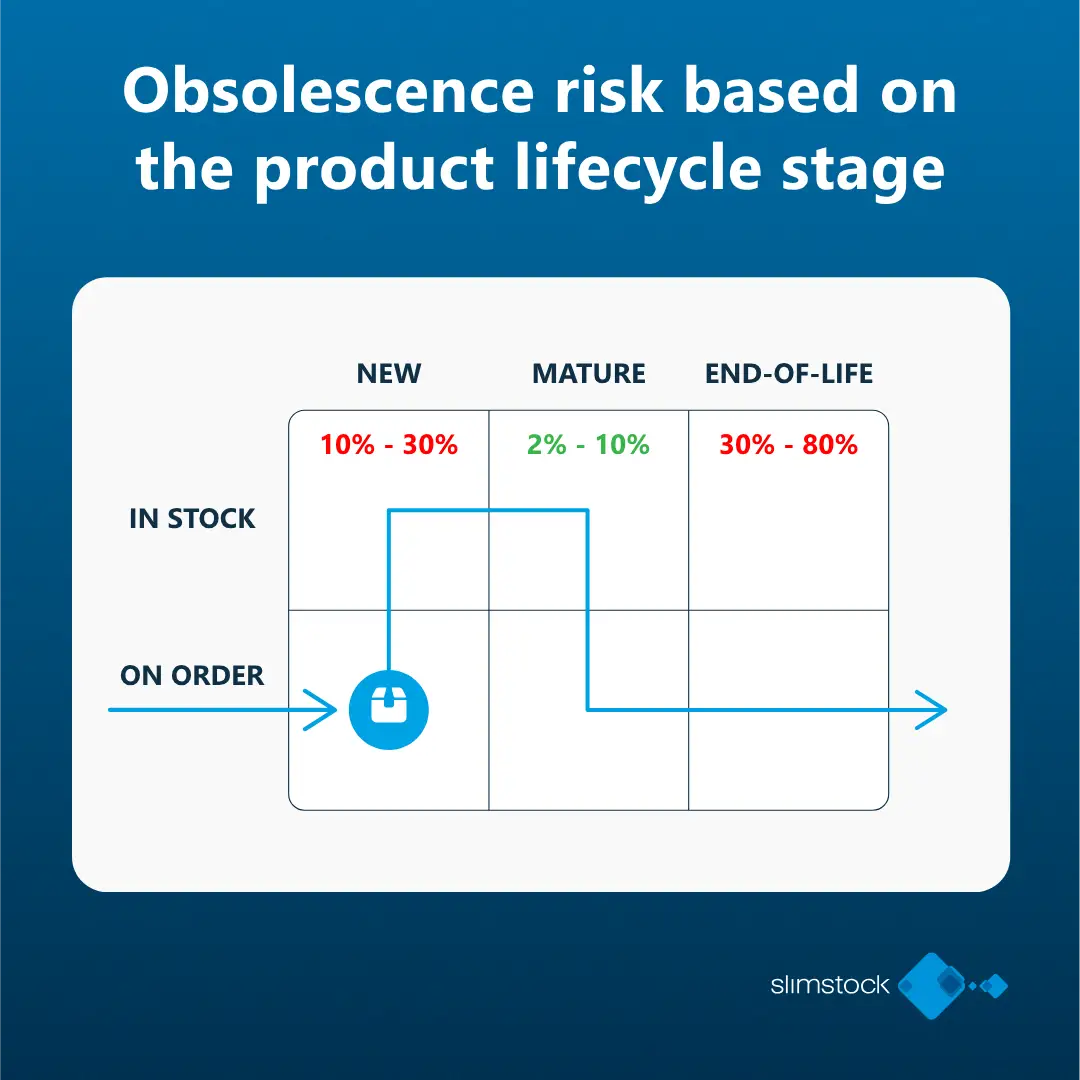

Risk of obsolescence depending on the phase of the life cycle

The following graph shows the percentages of risk of obsolescence of products depending on the phase of the life cycle in which they are found.

Notice how important it is to realise when a product is evolving from a phase of maturity to a phase of decline and to be able to change the model from ‘against stock’ to ‘on request’. You have to be quick and not be afraid to make the decision, because if you don’t, it could mean that the last order we launch ends up gathering dust in the warehouse.

Impact of restrictions and rules on obsolescence

Another aspect that can affect obsolescence is the restrictions that the supplier sometimes places on us in order to supply us with products and the conditions or logistics units. Once the supply needs have been calculated, they normally have to be adapted to certain logistical conditions. Either because they have been agreed with the supplier, or because of the intralogistics conditions of our company.

What are the most common adjustments that we find?

Supplier restrictions

Adjusting to minimum purchase quantities (MPQ), that among all the items we buy from the supplier we fill one of their shipments (a lorry, a container…), that the order reaches a minimum amount so as not to have to pay carriage. Although be careful with this last point, as we often increase the order in large quantities and what we save in carriage we end up paying for with the extra carrying costs.

Also beware of the occasional offers we may receive from suppliers, where they get our attention thanks to an attractive price, but on the other hand they require us to purchase in excessively high quantities. Whenever we analyse a supplier’s offer, we should take into account the coverage involved in accepting it and also put this criterion in the balance. And finally, the type of merchandise flow: counter stock, direct, cross-docking and just-in-time.

Internal restrictions

Internal restrictions, such as the desire to smooth out the order intake schedule at our logistics centre and avoid peaks and troughs and the impact this has on the staff I have hired for these tasks.

Indicators to identify demand trends

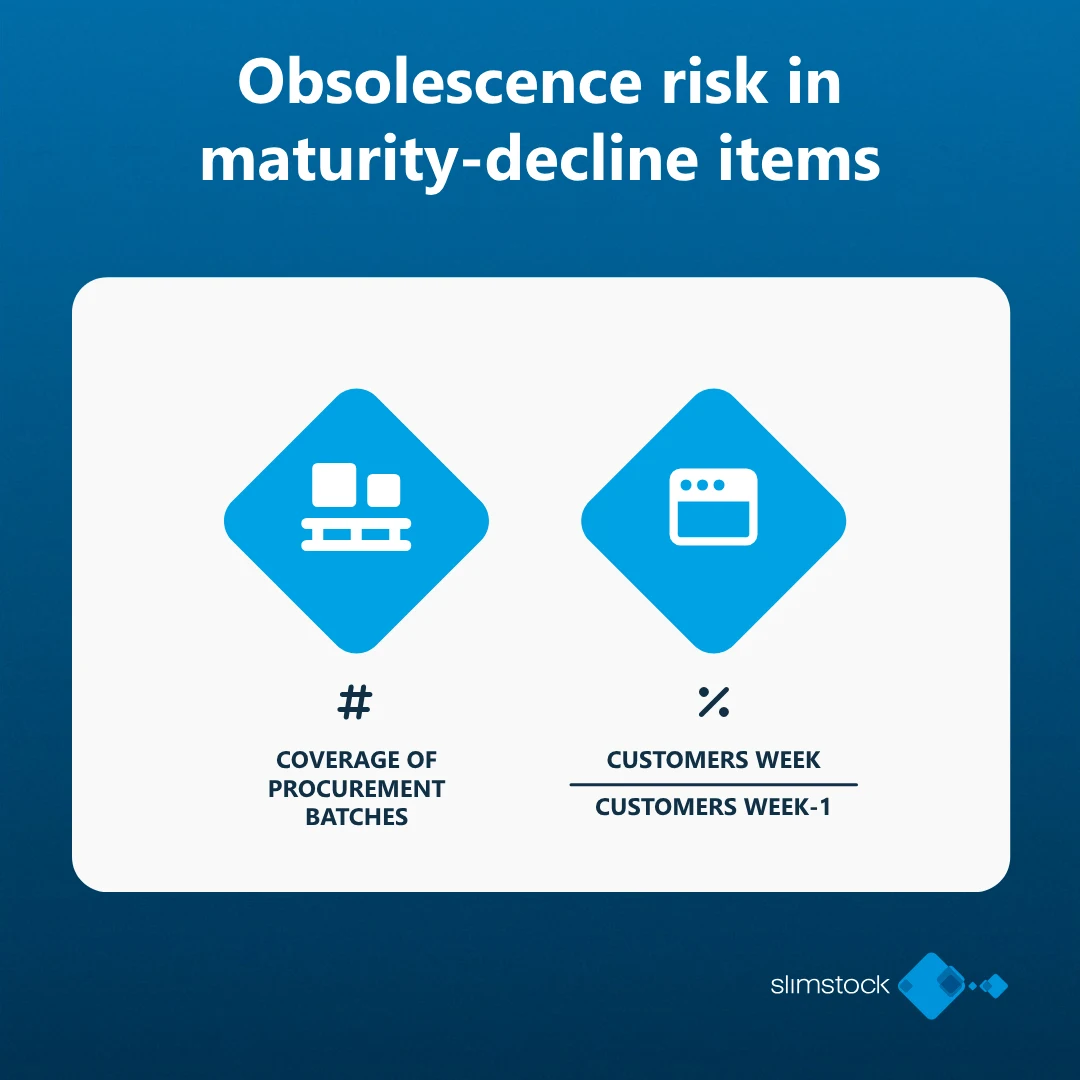

Let’s review the main indicators to keep updated in order to quickly identify the decrease in demand for our products. We are going to focus solely on the two phases of risk management: introduction and decline.

KPIs to consider during product introduction

As we saw earlier, we recommend introducing items with local suppliers whenever possible. They tend to be much more flexible and do not usually require such high minimum purchase quantities. What should we take into account during this stage of the life cycle? Precisely that coverage of purchase lots based on the updated forecasts we have and also the percentage of customers I gain or lose each week for that reference. If in the introduction phase I am losing customers week by week… be alert.

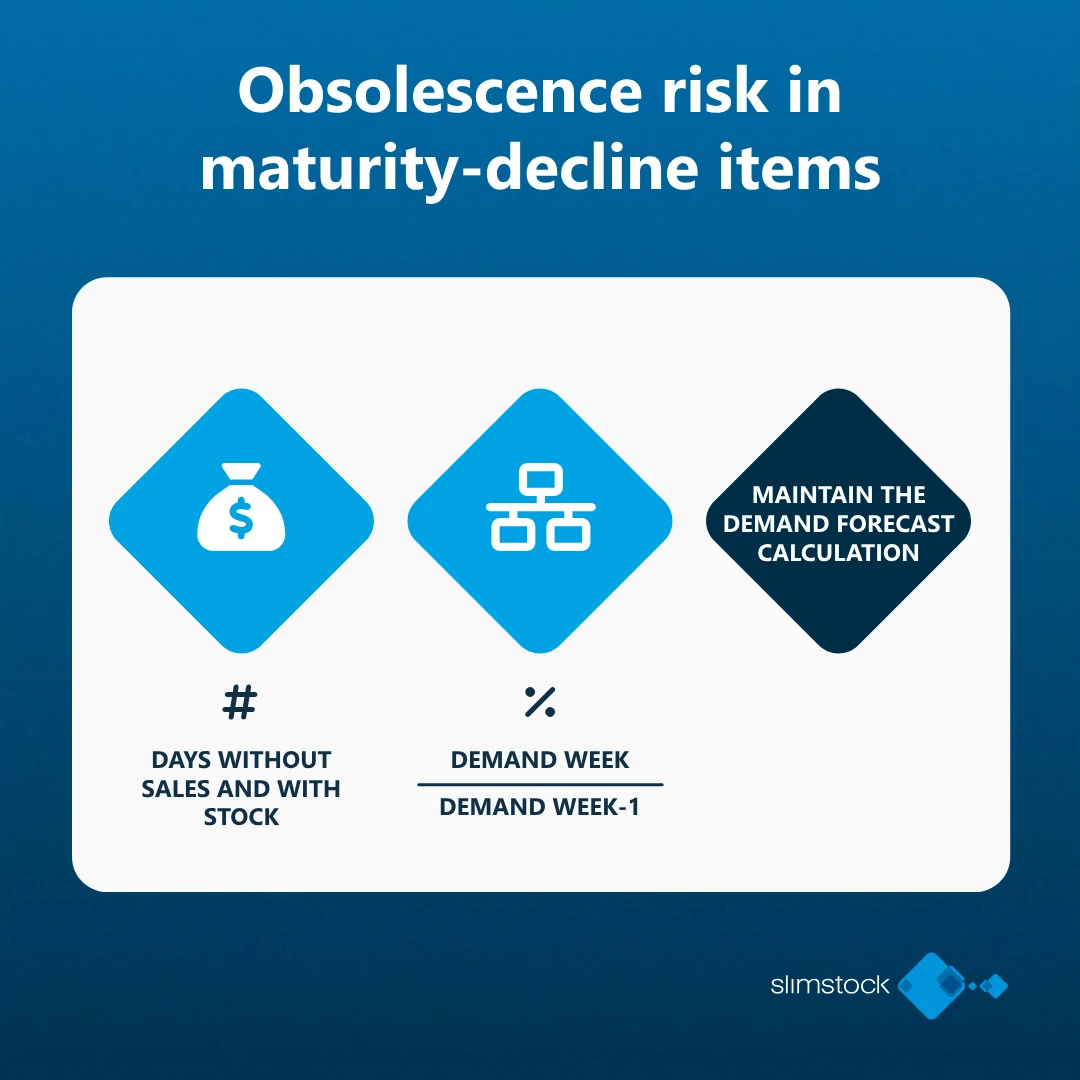

KPIs to bear in mind during the decline of products

The other risk phase is when a product goes from maturity to decline. It is important to continue forecasting (forecasting) products. Just because we are dealing with products whose demand is declining, we are not going to forget to forecast the demand for these products. It is still very important. So what are we going to measure? I recommend these two simple indicators: Measure the number of days without a sale and the number of days we have had stock (both weekly and monthly) and measure the percentage of loss of demand between weeks. Again, let’s start here and see the results obtained.

For those of you who want to go further, what other indicators can I measure? Order lines, available stock coverage, difference between CMC quantities and real need, breaking bulk, … the behaviour of equivalent references, successor items, taking ABC into account, erratic demand patterns … or items that I manage on request and have a high CMC … among others. As you can see, there are many aspects that I can measure to try to minimise product obsolescence.

Conclusion: What should we take into account to minimise obsolescence?

By way of a final summary… what else should we take into account when minimising the risk of obsolescence? The following points.

- The seasonality of the product. Working with averages should not be an option if you want to be efficient. It is a huge source of future obsolescence.

- Promotions. All planned promotions must be taken into account and added to the forecast for demand for the product as additional demand.

- Product life cycle. It is not the same when a product is growing as when it is in a mature phase or when it is in decline near the end of its life.

- Planned product withdrawal. It seems obvious, but we come across cases where it is not so obvious… if you know you are going to withdraw a product in June, don’t assume the demand will last until the end of December.

- Safety stocks by product group. This reduces the stock level of the products in the group in question and, therefore, helps to be more surgical in supply management.

- Multi-supplier option. Allows the supplier to have more leverage than us in the management of certain products.

FAQs about Obsolescence & Obsolescence Management

What is obsolescence in inventory management?

Obsolescence occurs when stored products lose their relevance or demand in the market, generating unnecessary costs for storage and loss of value. It is mainly caused by excess stock, changes in customer preferences or technological evolution, among other reasons.

What factors should be considered when deciding between stocking or ordering products?

The decision depends on several factors such as the frequency of sales, the stability of demand, the profit margin and the ability to return products to the supplier. Stocking is ideal for products with high demand, while ordering is more suitable for items with uncertain or declining demand.

What are the main phases of the product life cycle and their impact on procurement?

- Introduction: Order-based procurement is recommended to minimise risk.

- Maturity: This is the most stable stage, ideal for applying optimisation strategies such as EOQ.

- Decline: It is crucial to reduce the service level and slow down procurement to avoid surpluses.

What key indicators help to identify trends of decreasing demand?

Some indicators include the number of days without a sale with available stock, the percentage loss of weekly demand and stock coverage greater than two coverage periods plus safety stock. This data allows for quick action to adjust procurement and minimise losses.

How can companies manage slow-moving and obsolete stock?

Companies can manage slow-moving stock by identifying items with low demand using indicators such as days unsold and excess coverage. When a negative trend is detected, the level of procurement should be reduced, discounts or promotions should be implemented to liquidate inventory, and management models based on orders should be used for products in decline. In addition, exploring alternative channels such as outlets and maintaining dynamic forecasts helps minimise losses and optimise inventory management.