Table of contents

Table of contents- Breaking bulk: a KPI for measuring the value generated by the supply chain

- What is breaking bulk?

- How is breaking bulk calculated?

- Breaking bulk of the assortment and value creation

- Breaking bulk differences by sector: some examples

- Conclusion: breaking bulk, an essential KPI for making decisions about your product range

Overview

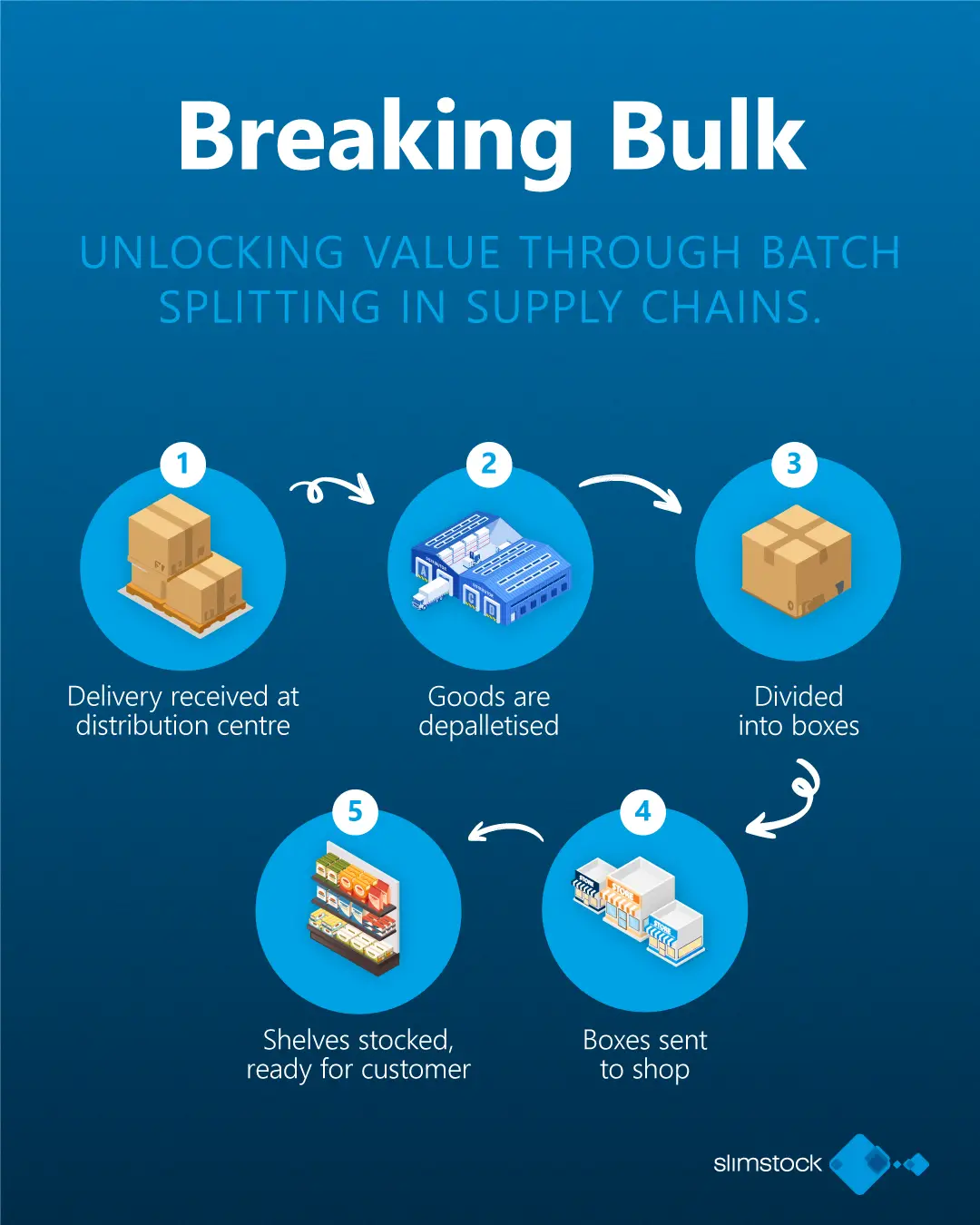

Breaking bulk is dividing large supply chain loads into smaller consumer units, measured by the ratio of outgoing to incoming lines (a key KPI). A higher ratio reflects better value creation and commercial opportunity, but the ideal level depends on the industry (e.g., low for raw materials, high for e-commerce).

You go to the supermarket, stop at the rice section and scan the shelves from top to bottom: long grain, bomba, round grain, basmati… Finally, you decide on brown rice and put it in your trolley. Before ending up in your weekly shopping basket, that packet of rice has travelled through the entire supply chain, from the field where it was grown to the supermarket shelf. Various players have been involved in this process: the producer, the distributor, the retailer… But how do all these companies manage to make a profit margin on the same product?

Well, the fact that different links in the supply chain can make money from buying and selling the same product is largely due to their ability to purchase large batches of product and resell them in smaller units.

What is breaking bulk?

In the context of the supply chain, breaking bulk is understood as the process of “breaking up” larger loads into smaller fractions so that the product can reach the consumer in an accessible format and with added value. In other words, without this process, rice would continue to circulate in sacks weighing tens of kilos, and it would be very difficult for an end customer to take it home in a reasonable quantity.

Furthermore, breaking bulk is not just a matter of convenience for the consumer. It is also a strategic lever for companies involved in the supply chain, as it allows them to tailor their offering to the needs of different market segments. The same batch of rice can be transformed into multiple presentations, from family-sized packages to individual formats, maximising the product’s profitability and generating more commercial opportunities throughout the distribution network.

How is breaking bulk calculated?

Breaking bulk is calculated using a very simple ratio: the number of outgoing lines divided by the number of incoming lines. The higher this value, the better the process will be, in principle. Breaking bulk reflects the extent to which a company is able to transform larger loads into split orders for different customers.

Let’s continue with the rice example. Imagine that a distributor receives 100 incoming lines in the form of pallets of rice sacks. From these sacks, the distributor splits them up and sells 1,000 boxes of 1 kg rice packets to different retail customers. In this case, the breaking bulk would be 10. This ratio directly shows the chain’s ability to generate value by multiplying the commercial opportunities of the same initial batch.

This metric is useful because it connects the operational with the economic. A high breaking bulk means that the stock purchased is converted into more transactions, which implies more inventory turnover and potentially more margin. Conversely, if the ratio is low, it may be a symptom of inefficiency: perhaps purchasing volumes are inadequate, or the ability to split the load according to actual demand is being wasted.

Breaking bulk of the assortment and value creation

Analysing the aggregate breaking bulk of an entire assortment reveals how a company generates value across its product portfolio. To gain meaningful insight, results are typically grouped into ranges.

In the case of Slim4, our software usually works with the following ranges:

- High range (≥25): each input line becomes 25 or more output lines.

- Medium range (10–25): moderate level of fractionation.

- Low range (1–10): limited breaking bulk.

This classification is key because it helps to identify where the leverage for profitability really lies: products with high breaking bulk not only multiply transactions, but also make logistics more profitable, optimise handling and offer the market more accessible and attractive formats. On the other hand, those in the low range require more detailed analysis, as they may be consuming resources without contributing in the same way to the company’s margins.

Want to take your supply chain performance to the next level? Discover how Slim4’s Network Balancing module helps businesses synchronise inventory, optimise stock levels across networks, reduce costs and enhance service levels.

Breaking bulk differences by sector: some examples

The value of breaking bulk varies greatly depending on the type of product and the nature of the market. Not all companies need or benefit from achieving very high breaking bulk ratios. While in some sectors, fractioning adds little value and increases the cost of the operation, in others it is precisely what allows them to be competitive and respond quickly to demand. Let’s look at how this KPI behaves in different production and commercial contexts, from the lowest to the highest degree of fractioning.

Industrial and raw materials sector: low breaking bulk

In industries such as metallurgy, chemicals and raw materials, breaking bulk is usually very low, even close to 1. In these sectors, products are marketed in large volumes — steel coils, oil drums, fertiliser bags — and their fractionation before reaching the customer is usually minimal. Additional handling generates little added value and, in many cases, increases costs or compromises product safety. Therefore, the focus for achieving operational excellence is on increasing transport efficiency rather than fractionation.

Mass consumption and food distribution: medium breaking bulk

The mass consumption sector, especially in food and beverages, has intermediate ratios. Here, there is a significant fractioning process: manufacturers sell in large batches to distributors, who then transform those input lines into multiple output lines to supermarkets and shops.

Large e-commerce: high breaking bulk

An example of companies with very high breaking bulk are large e-commerce portals. In these environments, a single input batch is converted into hundreds or thousands of individual output lines. Consider, for example, companies that purchase containers filled with the same product and then sell them to the end customer via the internet. The key here is the logistical capacity to split quickly and accurately, as the value lies not so much in the product as in agility and availability.

Conclusion: breaking bulk, an essential KPI for making decisions about your product range

Breaking bulk is not just an operational metric but a strategic indicator for managing your product range. Measuring the ratio between input lines and output lines reveals the extent to which a product generates value when it is broken down and marketed in different formats.

Through breaking bulk, supply chain and purchasing teams can make better decisions: adjusting service levels by family and, above all, prioritising those products that add the most value.